Baba Henry Chan (whom I will respectfully call Uncle Henry), represents the Babas I remember from my childhood. They included my Koh Poh Beng Neo’s husband and my father (except when he harangued the hotel chef for the salty soup at my wedding). I can only imagine that Baba Lee Kip Lee, president of the Peranakan Association in Singapore, was another stellar example. (Though I had never met him, I see that quality now through his sons.) Uncle Henry, like these men before him, is soft-spoken, polite, considerate, unassuming, gentle in demeanour and articulates in a thoughtful, measured manner. These traits embody the best of Baba decorum. Uncle Henry exemplifies this with regal bearing.

I was therefore truly honoured that he obliged with a written interview. This is in conjunction with the 40th anniversary of the Baba Nyonya Heritage Museum in Melaka on July 19, established by Uncle Henry and his late brother. The museum is the Chan family’s ancestral home, carefully restored to showcase the Peranakan legacy over several generations. It is the first of its kind.

Read on about his childhood when Melaka had a dreamy, golden era yet untouched by a world war. Find inspiration in how he set up the museum and ponder about Uncle Henry’s thoughts about the past and the future.

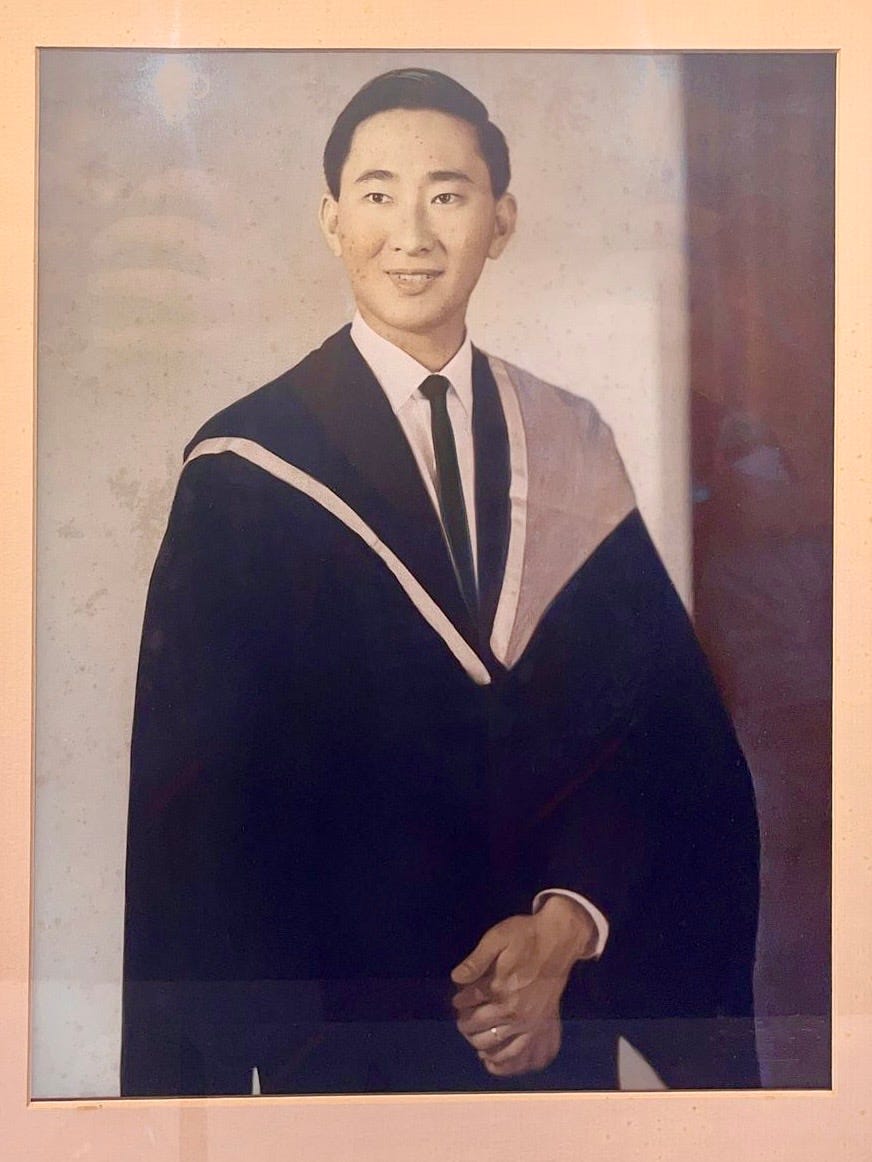

Memories from the Silent Generation, Henry Chan Kim Cheng, born in Malacca in 1934.

You co-wrote the book “Stories of one Malaccan Family” with your daughter Melissa. It is a heartwarming compilation depicting childhood memories of you and your siblings. For those who have yet to read this book, could you describe your family and childhood in Malacca?

I think my parents may not have expected my birth, as my elder sister Irene was nicknamed Bung Su which usually refers to the last child. But I instead ended up being the last child of the family.

Growing up in such a large family, of eight children, as was customary during that time, two of my other siblings and myself were raised by my Aunt “Mama Tanjung”. She took care of me until I was four or five years old, and I grew up in my maternal grandmother’s house on Tengkera. We each had our own full-time amah to take care of us. When I was supposed to return to own my parents, I have been told, I was reluctant and threw all my clothes into the well.

My early primary education began in Bandar Hilir English School. During the war (to our delight) we were absolved of any formal education, and when World War II ended, I attended Tengkera English School, and thereafter Malacca High School. My favourite sport in school was badminton, and I also have fond memories of being a boy scout. My favourite memory was attending camping activities. There was a bungalow besides a large area of beach in Tanjung Kling, and there we would have camps where we were taught basic survival skills. To this day I still have my boy scout certificate!

You are the youngest child among eight children. What advantages and disadvantages did you experience as the youngest child?

Advantages:

My parents paid more attention to us younger ones (Kim Sinn, Irene and myself).

Special memories:

Father (Ba) was a serious person, I didn’t communicate with him much, more with mother. But every year end, we had to present our report cards to father who would be seated in his rocking chair in our house in Klebang, reading his newspaper. If we didn’t do a good job, we would get a spanking (rotan) and scolding from Ba.

Memories with Nya:

My favourite memories of spending time with mother (nya) would be on a trishaw, when she went to play the card game, cherki, with the neighbours down the road, or to the hairdresser. I remember the old-fashioned curling contraption at the saloon. Nya used to fashion her hair into two buns on either side of her head which was fashionable during that time, and she didn’t cut her hair.

Us children spent more time with mother. If my memory serves me well, she used to give us 20 or 30 cents daily for pocket money.

I also remember we had two chung poh (cooking assistants) staying with us.

What was it like to grow up in the house in Heeren Street? And what about the neighbourhood along that street? (Any special recollections of hawkers, friends, games played.)

I didn’t grow up in the house on Heeren Street, but for a short period after World War II, the family did spend some time there. I remember itinerant peddlers selling Tok Tok Mee, Mee Siam, on the street. We hardly knew our neighbours, but I do remember the maternity clinic next door (today it is the NUS-TTCL center). I was one of the last to be delivered by Dr. Ong who was then the owner of the clinic. Indian men riding on bullock carts would pass by, selling cow dung as manure. The rickshaw men (mainly Chinese) would bring mother to other families to play cherki. We hardly went out to eat. After World War II, there was only one main restaurant in Malacca, at the junction of Jalan Bunga Raya and Newcome Road (and Munshi Abdullah).

What were your memories of living through World War II?

Because of the fear that the Japanese were going to bomb the town, we stayed in Klebang with other families. Just before the end of the war we went to the rubber estate for refuge.

During the war, we used to go the Straits of Malacca sea, which was literally our backyard, to dig for clams (cari kepah). Father had a kelong (an entrapment for catching fish) which caught a lot of ikan kurau (Indian threadfish) and all sorts of other fish; mother would make salted fish ikan masin, as a dish from the caught fish. I remember making and flying kites with my elder brother Harry. He would coat the kite string with glass, glued using a concoction of egg yolk and dipped into shards of broken, pounded glass. We would venture down during low tide, and with the strong winds, we would use our kites to have a friendly game of attacking the other local Malay boys who were also playing kites by the beach. Other childhood games were involved with were playing marbles and gasing (spinning top).

I also remember our chung poh was good at making baskets from the bamboo plants in our compound. Our house compound also had a lot of coconut trees, and father made a machine to grind the coconut, to turn into coconut oil. We used that also to make soap and for our cooking oil. With father supervising chung poh, we would watch and help.

I remember father also had a friend who taught him how to grow mushrooms from padi (rice-plant) stems, and we enjoyed eating those mushrooms!

How did this idea come about – of turning your family home into a museum?

From the 1950s, until the 1980s, the house was empty most of the time and being used as an office, or we would pay a visit for ancestral prayers, or during Chinese New Year we would all come back to clean the house. It was my eldest brother’s idea to turn the house into a museum in the 1980s. If my father was alive, he probably would not have agreed, but by that point only my mother was consulted.

Most of the furnishing on the ground level of the house has been placed in the same way the family would have used the spaces, whereas the upstairs (lohteng) has been arranged in a more gallery-like manner, this was done when my brother was managing the space. Almost all the furnishings are original to when the family lived in the house.

I took over managing the museum when my eldest brother Chan Kim Lay passed away.

What were some of the challenges in putting this house together to become a museum? Where did you source the interiors? Did you have to do a lot of repairs and refurbishment?

When I took over managing the museum, structural restoration needed to happen- termites had been eating the roofing beams, there was a leakage. We found a trustworthy local contractor who was familiar with the renovation of these old buildings, Mr Loo. With my architectural background, I oversaw the renovation. We added central air conditioning to the main entrance and some glass coverings for high traffic areas to protect visitors from rain, and commissioned artists to re-do some of the wooden fretwork panelling that was stolen after World War II.

What have been some of your proudest moments since the museum opened to the public?

From 2012, bringing the building up to its former glory and re-structuring the internal administration of the museum to operate accountably for shareholders (who are family members).

What changes have you witnessed in Malacca over the years?

There are more cars on the road, compared to the days of bullock carts and trishaws passing by.

One of my favourite memories growing up as a young teenager, was being able to go for picnics with friends to Tanjung Bidara. We would group together and spend the day by the beach, both girls and boys.

How can younger Peranakans keep the cultural heritage alive?

Organising more activities such as celebrating festive occasions like birthdays in traditional ways (serving kueh ih), and enabling the older generations to share recipes and stories of the way of life to younger generations.

What do you miss most about the good old days?

It was much simpler!

Life was much less digital: I do remember after World War II, my eldest brother Kim Lay making a simple radio from what was called a “crystal radio set” which he had learnt through a correspondence course. I also remember connecting with strangers all over the world through letter-writing, to exchange stamps from other countries. I had quite a collection of first day letter stamps. Memories of buying Beano and Dandy comics from the Lim Brothers Bookstore in town, and one of my other hobbies that I picked up as a young adult was photography, I had a Zeiss Ikon bellows camera, and I remember in the 1950s my brother Harry had created a darkroom in a storeroom upstairs of the house on Heeren Street, where we developed the film. Later on I invested in a Kodak Brownie 8mm Film video camera.

What are some of your favourite Peranakan kueh?

Pang Su Si was my favourite growing up made by Mama Tanjong my aunt, kueh genggang (layer cake) ta chi Poppy (eldest sister Poppy) used to make red and white, nya made putu mayam (string hoppers). But my favourite sweet dessert is making ice cream, which we made ourselves. The machine my siblings and I used is now a feature in the museum.

In your book, you write about going to the movies at the Capitol theatre in Malacca. Do you still like to watch movies? Name a few of your favourite movies of all time.

The movies I remember most were the black and white Tarzan and Batman shows in the late 1940s-1950s. Chaperoned by my elder brothers, we enjoyed the matinees which were cheaper than the normal shows (they cost 20 or 30 cents). I will never forget entering the theatre through the thick curtains and being brought into the main hall that was filled with smokes, through the hall from everyone’s cigarettes.

I don’t watch movies anymore.

Of all the museums you have visited in the world, what would be your favourite and why?

I would say my only favourite museum is the Baba Nyonya Heritage Museum.