Today marks Mother’s Day. Last Sunday, May 4, marked the 33rd year since I entered the workforce. However, I have been a stay-at-home mother longer than I have officially worked. My children have no recollection of me coming home every evening with a bag loaded with a laptop and office documents, dressed in a smart outfit or a shirt with a pussycat bow, longing to wipe off my make-up. It never quite happened, definitely not after they were born.

Many of my friends gave up their office careers too, in the name of childcare. While we hired part-time nannies and cleaners, the setup we faced in New York differed from my counterparts in Singapore. A full-time housekeeper would require a room and the higher salary would be more prohibitive. On a more practical note, the children would gradually spend more time in school, leaving a full-time helper with less to do to justify a monthly salary. In most cases, it would be the mothers who do the school runs and after-school activities.

Hence, my children and many of their friends do not relate to their mothers as having been, once upon a time, bankers, lawyers, traders, advertising managers, fashion designers, publicists, with many of us armed with advanced degrees. Where did I meet my “mommy friends”? Baby groups, volunteering in our children’s schools, or through mutual friends. As the children grow up, a few of us have gone back to work full-time, others have sorted out a part-time work schedule, a few are tinkering with new businesses. I often wonder if I might not be a role model in today’s landscape where women hold high-powered jobs and professions.

Given my personality traits, stamina and temperament, it made more sense for me to stay at home because my firstborn baby needed medical attention and a circuit of doctor visits. The rhythm set in and I never returned to an office, somewhat apprehensive that I might never quite reintegrate into the workforce. Besides, my mother had stayed at home and in many ways, I did not know anything differently from that.

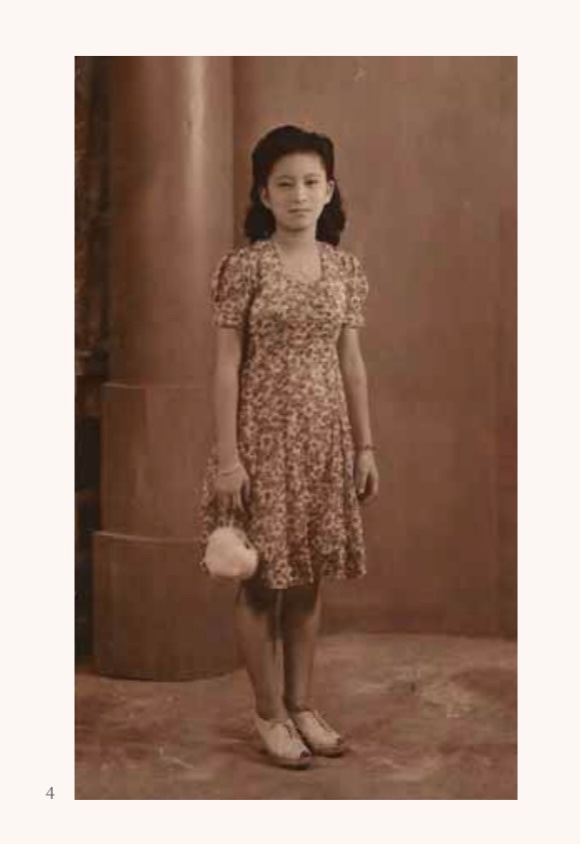

Her childhood interrupted by WWII, my mother did not complete her primary school education, with a belief enforced by a father who insisted that privileged girls like her should be more genteel and stay at home. (Funnily enough, her little sister studied all the way and ended up becoming a secretary until she retired in her 60s.) My mother straddled the era when a few of her bright counterparts obtained university degrees, a few went as far as Cambridge and topped their degree course, for example, Mrs. Lee Kuan Yew.

As I described in my book, my mother “had to cope living in a world that would soon transform significantly in her lifetime-when it became the norm to read newspapers, watch television, decipher adverts, and converse with friends who, unlike her, went on to higher education. She made up for any shortcomings by being very observant-she deduced information from news images and analysed and memorised everything,. Sometimes, she would ‘make do’, such as with the church hymnbook, when she simply hummed and mumbled along with the tune.”

I can only imagine what a struggle it was for my mother. If I could sometimes feel caught in this setup, of simply being cast as a housewife, or worse still, a “taitai” (lady of leisure), I can only guess that she had her frustrations too, from time to time. By 50, she was a grandmother. By 60, she had at least four grandkids dropping in when my working sisters needed someone to help for the day. My mother once walked out of the house. My sisters and I got rather frantic, searching for her. All she said was, “Gua mo tarek napair.” (I need a breather.) Thankfully, she returned a few hours later, committed to continuing as wife, mother and grandmother. You cannot just shake off those roles, can you? It’s a job for life, like it or not, and you don’t get hired or fired for it.

As much as she was compromised by her lack of academic education, she compensated for it with loads of wisdom, patience and experience. She bought me my first book which opened up a world of knowledge. She forged a close friendship with my primary school principal so that Miss Yap was just a phone call away if she needed advice on my education. My mother let me guide my own path. When I told her I wanted to start going to church, she simply commented, “You have to be committed for life.” I am tremendously grateful that she gave me a wide latitude to forge my path.

My mother was just a representative of her generation in transition. Part of her legacy was to leave behind her recipes, kitchen work tools and the memories of food lovingly cooked to bind us as a family. Enough for me to write a book about her.

What legacy do I leave? An old friend told me that my best calling was to be a stay-at-home mother. Any “career” is only as fulfilling as we want it to be. Some thrive solidly in their professional lives. Others like me constantly carve our way. In fact, I spent this afternoon at my business school reunion, attending a workshop on discerning my purpose in life - an amalgamation of what I want to do, can do and should do.

Someone mentioned recently in a bible study group that we should “live each day as if it is our last.” It might sound alarming. Those of us who are mothers, can mark our life’s work by the milestones in our own children’s lives; birth, kindergarten, college graduation, wedding being some of those rituals. My mother set a blueprint that I can add accents to.

Time seems to pass too quickly in our tech-laden age. The legacy we leave behind is a life well lived, productive enough to establish memories and impart wisdom to those we love, and eventually leave behind.