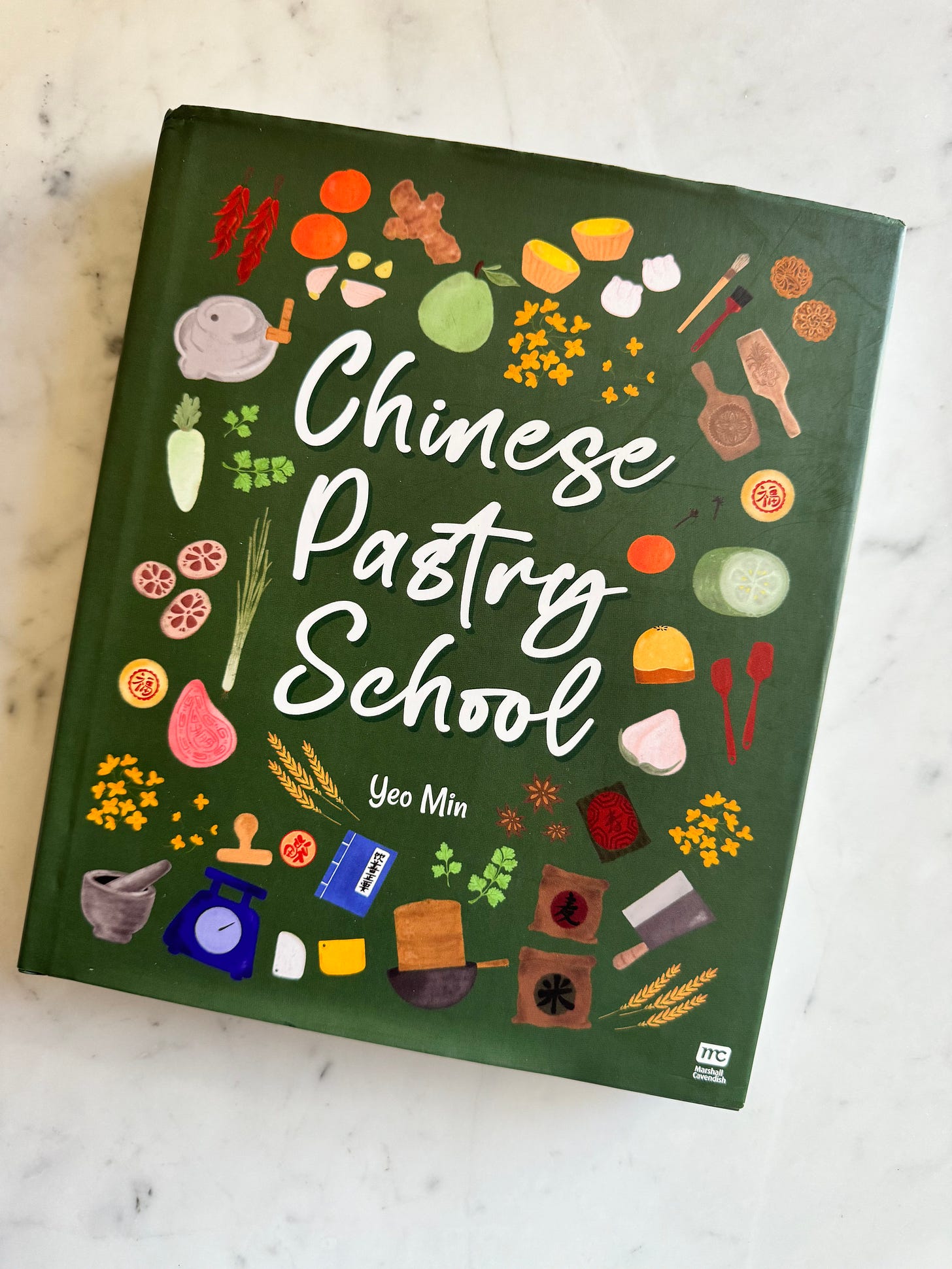

It’s been a while. With good reason. Yeo Min, the author of the award-winning cookbook, “Chinese Pastry School” had been travelling to London and European cities to promote her book and her homemade pastries.

When Yeo Min once wrote to me, I did not understand her text and had to have my Gen Z kids translate it for me. She comes with youth, energy and vision. Yeo Min put together a comprehensive “textbook” about all the pastries we love to eat but never dared to make at home. And she has coupled her background in social work to venture into initiatives that go beyond profits, seeking to build a community and a collective food memory. Yeo Min represents the next generation of food writers coming out of Singapore and she’s leading the charge.

You had studied Social Work in London. How did you transition to writing an award-winning cookbook?

It was quite the journey! I wouldn't actually have entered the kitchen voluntarily if I never went abroad for uni, nor had that moment of "awakening" about my cultural identity.

Living alone in London on a student budget meant having to make most of my meals. I had quite a lot of time back then, because most of my classmates were mature students, so my uni experience was a lot less active and social than I think it would have been if I'd stayed in Singapore. I spent my "extra" downtime in the kitchen, using cooking as a way to destress. My repertoire grew year on year, as my accommodations' kitchens got nicer and my appetite for learning new techniques grew. I picked up Harold Mcgee's book, “On Food and Cooking”, sometime in my second year, and that was such an eye opening piece! After working for 2 years, I realised that I need to engage in more creative work.

Thinking about identity is a huge part of social work training, because it influences the way we interact with service users. This training stuck with me, and became something I often thought about even outside the context of social work. In pastry school, I'd think about my identity as a Singaporean pastry chef. This led me to become curious about Chinese pastry, and ultimately dive into the topic.

What was the most challenging Chinese pastry that you learnt? Who did you learn it from?

I'd say that heong piah or beh teh saw (Maltose Pastry) is one of the hardest! I didn't get to learn it from anyone in particular, but had discussions with Chef Pang about how to best bake them without the piahs bursting in the oven. This piah taught me that there are lots of recipes online that may not work, and that oven setup is important when baking specific recipes.

How did you go about testing your recipes? Were they solitary moments? What went through your mind during all that time?

I worked on my book during Covid, and funnily enough I actually caught Covid right when I started working on the book full time. I'd just completed my internship at a kueh factory where I was exposed to the virus many times but was somehow immune - then caught Covid right after leaving! I made the most of my two week recovery testing medicinal dessert soups on myself, with groceries I asked my fiance to drop at my door!

After a few months we decided to get a puppy (Lemon!) and she became my default book buddy.

You say that you “flunked Chinese”. How then did you manage to decipher all the Chinese literature in the research you conducted for this book?

😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂

I'd like to think my Chinese has improved! I didn't just flunk Chinese actually, I also flunked chemistry and gave up on biology - both of which come up quite a bit in food science.

I've always been good at studying something I saw the purpose in, so these subjects made no sense to me in school. Like, I've never had to use formal Chinese all these years! And whatever crystallisation we learnt in secondary school also didn't seem helpful back then - but it suddenly made sense when we learnt to deal with sugar in pastry school.

For the very complex traditional Chinese bits in this book, I used a combination of Google translate, help from my linguist bestie, Amber, and spent time re-reading sources. I also looked up existing translations and cross referenced a few versions to make sure I understood the text correctly.

Where and how did you research?

I worked from home, mainly! Thank goodness for Amazon and Taobao that sent books to my doorstep. There's also a plethora of recipes and traditional tecchniques being shared online (mostly in Chinese), so I made reference to those too.

I initially wanted to make study trips to China, but the country didn't open its borders in time for my submission. I was, however, able to visit Chinatowns in London, Boston, and New York to observe and taste some pastries that are uncommon in Singapore. My first bak tong gou (White Sugar Cake) was actually from Boston.

What is your favourite Chinese pastry?

I don't have a particular favourite! My favourite one to make though, is mung bean Ang Ku Kueh (Red Tortoise Cake). And the recipe that always mesmerises me is maltose syrup.

What can Western pastry learn from Chinese pastry? And what can Chinese pastry learn from Western pastry?

Two things are particularly "missing" from Western pastry curriculum - the use of starches and the use of food as medicine. What used to both amaze and confuse me was how different kueh makers could create such a variety of textures by working with different starches; or by using different quality, sized, and aged grains create something new. I never fully understood starch gelatinisation (we came across this term in pastry school) until I dived into the world of kuehs. The reference to TCM (Traditional Chinese Medicine) is another huge piece in the Chinese pastry world. I think many people misunderstand how Chinese pastries should be eaten, so they complain about how "dense" or jelak (sated) the pastries are.

As for the other way round, I think Chinese pastry could definitely take a few presentation and marketing tips from the West! This is purely from personal observation — I think the way Western pastries are presented tend to be a lot more fancy, so it’s easier to sell them to customers who are looking for beautiful pastries to gift. The settings for serving Western pastries also tends to be a lot nicer, like in hotel lobbies and such. I’m not saying that Chinese pastries are not already great as they are, but perhaps more can be done to generate interest in the pastries themselves! I dream of a future where Chinese pastries are valued as much as Western ones, and I guess in this day and age, the way to achieve that is to work on presentation and marketing.

What are your thoughts about Asian fusion pastries?

Ooh. I think fusion pastries are okay, as long as they don’t spiral into confusion!

I love that many Singaporean pastry chefs are infusing Asian elements into their bakes. The only thing I wish for is that fusion pastries don’t replace traditional ones entirely. Fusion bakes are definitely a good opportunity for consumers to get acquainted with Asian flavours in a very non-intimidating way, but I’d be careful to throw just anything and everything together. There are definitely instances where I have seen chefs appropriate food culture — for example, by making something that looks like a traditional kueh or piah, but has NONE of the elements of those items in flavour or texture.

That said, I’m also quite intrigued by the constant innovation of fusion food in Singapore. When you look at old cookbooks or photographs, it seems that fusion foods have long been around! That’s quite cool to know, and I wonder if it’s just in our Singaporean DNA to fuse different elements together, because of our history of immigration, multiculturalism, and colonial history.

If you could concoct one, what would it be?

I’ve actually just made a few for my ongoing popup at Baker X! I’m occupying a space in Orchard Central until early December, and set up the space as a food museum. I wanted to introduce heritage flavours in a more welcoming way (especially to younger children!) so I came up with a few fusion-ish bakes!

One of my favourites is the Bandung tres leches, which essentially transforms the Central American dessert of milk-soaked cake into a “Bandung” soaked one with the addition of rose syrup. Another one I really like it the kueh kosui crumble bar! I love kueh kosui, and I wish more people would try it. But friends my age or younger tend to dislike kuehs of that texture, so adding crumble to it makes the kueh more inviting.

Now that you are getting married, what food traditions will you like to establish as you build your own family?

I’m definitely making my husband-to-be make bak zhang (rice dumplings) with me every year! I started making them in university, and tried to get my family to make them together when I came back from my studies. But they were not very keen because it’s too much work. When I met Gangyi, I learnt very soon that he’s quite a serious home cook! Since our first Dragon Boat Festival together, he’s been in charge of preparing the bak zhang fillings while I do the wrapping. It’s a lot more fun doing this with someone!

How important has your dog Lemon been in your culinary journey, from learning to bake to writing and promoting a book?

SUPER! Lemon has many jobs. To me, her main job is emotional support. But I think from her perspective, her main job is to help me clear any extra food when I test recipes! For example, when I make ang ku kueh and use sweet potatoes for the skin, she gets to eat all the extras.

Back to your social work experience. How do you hope to combine your passion in baking with working for a good cause?

I have two projects in the works at the moment!

One is just starting to take off — a food museum for Singapore. I’m starting small with this project and dream of bringing it to life in its own physical space in the future, and whatever the form this may take, it will be a community-centric space. Singapore’s food memories live in all of us, young and old, in our homes or out in restaurants and hawker centres. And we all have food memories, because eating and cooking take place every single day. I’d love to make this food museum a place where Singaporeans can reminisce, learn about one another’s food cultures, and celebrate our food history together! Part of this will involve reminiscence therapy for seniors, and offer older Singaporeans a place to share their legacy with younger Singaporeans (and tourists too!)

Another project I’m planning is a social enterprise cold kitchen model — but I won’t share more because I’m still in the process of pitching the idea to potential partners! :)

What advice would you give to anyone young like you, who wants to publish a cookbook?

Speak to as many people as possible about your idea, reach out to cookbook “seniors”, and definitely give yourself a fair shot!

What’s scary about writing a cookbook (or actually any freelance work for the matter) is not knowing how well we’re doing, because unlike in a traditional workplace setting, we don’t have bosses and seniors to guide us along. So a lot of the process involves identifying who these “seniors” are and reaching out to them for advice. Of course, they’re not obligated to reply us — but my experience has been really positive so far! I’d like to think that people who cook and write tend to be rather nurturing!

I also say to give yourself a fair shot — and by that I mean to really sit down and map out how writing a cookbook can work out for you. A few friends have told me that they wished they could do the work I do, but have no connections, so are not going to try. But I had no connections to begin with as well, and a lot of how I started out was through sliding into people’s DMs and sending cold emails to publishers. I definitely got ghosted by some of them, and that’s honestly the worst that could happen. So if you’re really keen on writing that book, go send those emails and slide into those DMs! If you never try, you’ll never know.